History

The historical roots of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot,¹ known in America as Kung Fu San Soo, dates back about 1500 years to the Temples in China. However, due to the constant upheaval in China’s history, many records have been lost or destroyed, leaving some questions unanswered. As dynasties were overthrown and Emperors changed, China was divided and sub-divided into various warring factions and each faction produced many different types of fighting styles. The art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot is a combination of some of these fighting styles, which emerged throughout the tumultuous history. The Martial artists throughout China’s history have been forced to fight for the Emperors or against them using their fighting skills. It is only due to their unique fighting skills, the monks and the martial arts are still in existence today.

The historical roots of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot,¹ known in America as Kung Fu San Soo, dates back about 1500 years to the Temples in China. However, due to the constant upheaval in China’s history, many records have been lost or destroyed, leaving some questions unanswered. As dynasties were overthrown and Emperors changed, China was divided and sub-divided into various warring factions and each faction produced many different types of fighting styles. The art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot is a combination of some of these fighting styles, which emerged throughout the tumultuous history. The Martial artists throughout China’s history have been forced to fight for the Emperors or against them using their fighting skills. It is only due to their unique fighting skills, the monks and the martial arts are still in existence today.

Although the martial arts came out of the monasteries, the monks are not the originators of the arts. The Buddhists religion is one of peace and not violence, so the monks would not have spent their time devising means of combat. However, according to Han and Tang law, soldiers were not allowed to leave their positions unless they died or entered monasteries. Many of these soldiers left their positions to become monks, but took their martial arts exercises with them. While they had become monks to leave their positions behind, they continued to train in the arts and eventually trained many of the other monks.

One of the monasteries that trained in the martial arts was the Kwan Yin monastery, in the village of Pon Hong, Guangdong Province in Southern China. The main reason these monks began to train in the martial arts was to protect themselves from bandits and outlaws. They traveled from village to village collecting supplies and donations for the monastery. Many times they were attacked by outlaws and killed for their supplies.

One young monk wgo trained at the Kwan Yin monastery was Leoung Kick. He was an orphan when the monks took him in at the age of 10. Leoung Kick was at the monastery until the age of 30, when he decided to leave. Upon leaving, he took with him the training and experience he had gained as a fighter in Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot, the fighting style which was developed by the monks at the Kwan Yin Monastery. He was the great, great, great grandfather of Chin Siu Dek (陳壽爵), a.k.a. Grandmaster Jimmy H. Woo.

Three generations later, Chin Siu Hung, following in the footsteps of his family, became a well-known San Soo teacher. Hung was a big man, both in stature and in size. He was 6’ 5”, 320 lbs., and the overlord of his province. As a practitioner of San Soo, he became a participant of the Lèi tái (擂臺) matches. These were competitions between martial artists from both Northern and Southern China. They were also great social events for martial arts experts. Hung was famous for issuing challenges to the entire crowd of practitioners. At these events, the participants fought on a raised platform, without railings, until their opponent submitted; the loser was often crippled and often the fights ended in death. When Hung issued a general challenge, there were rarely volunteers and the meeting became strictly a social event. Hung’s style of fighting was known for its crippling ability and few would challenge him.

In 1918, Hung’s nephew, Chin Siu Dek (Grandmaster Jimmy H. Woo), came to live in Hung’s province. At the age of 5, the family taught Dek “little fighting tricks.” When he turned 7, his formal training began. From the beginning, Dek was his great uncle’s prize student. He learned extremely fast and loved the grueling workouts on the hard floors. In his teens, Dek became a travelling teacher of the art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot. If someone in the province needed a grievance settled, Dek was the enforcer. When the village elders decided it was time for the young men to learn to defend themselves, Dek was sent to the village to stay for months and teach them.

In 1932, the Japanese invaded Mainland China. However, they did not take over the southern provinces at this time. Chin Siu Hung was 73 when they took over his beloved province. In 1942, Lo Sifu’s uncle was forced to answer a challenge to fight the regimental karate champion of the Japanese army. This was to be a public display of the power of the Japanese conquerors in front of the “poor villagers.” Under threat of the death of his people if he did not comply, he fought and defeated the Japanese champion in less than 20 seconds. He and most of his students were then killed by machine gun fire. This basically ended Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot (蔡李何佛雄武術) in Mainland China.

Fortunately, in 1935 at the age of 21, Chin Siu Dek had left Mainland China under the passport name Kun Haw Woo² and sailed for the United States on a steamship. There is much speculation as to the reason Dek used an assumed name, but we know from his memorial tape, he was not an American citizen and had to buy a passport in order to enter the United States. Had he not left, he would have suffered the same fate as his Uncle and his fellow students. The Japanese invaders could not allow any possible resistance force to remain alive. Dek carried the art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung to America and kept it alive, while many of the other fighting systems were destroyed by the Japanese. Mao Tsi Tung later eradicated many of the other martial arts styles, training books and monasteries when the Communist Chinese took over power from the Japanese at the end of WWII.

Fortunately, in 1935 at the age of 21, Chin Siu Dek had left Mainland China under the passport name Kun Haw Woo² and sailed for the United States on a steamship. There is much speculation as to the reason Dek used an assumed name, but we know from his memorial tape, he was not an American citizen and had to buy a passport in order to enter the United States. Had he not left, he would have suffered the same fate as his Uncle and his fellow students. The Japanese invaders could not allow any possible resistance force to remain alive. Dek carried the art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung to America and kept it alive, while many of the other fighting systems were destroyed by the Japanese. Mao Tsi Tung later eradicated many of the other martial arts styles, training books and monasteries when the Communist Chinese took over power from the Japanese at the end of WWII.

Jimmy remained in Los Angeles’ Chinatown after landing in the Port of Los Angeles. He worked a variety of jobs, as he became acclimated to his new home in Chinatown, but he still found time to teach the art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot to close relatives and friends. Later, he became an instructor at the Sing Kang, “cousin club,” a social/recreational organization. He also served as security for the residents and businesses in the area and sometimes acted as a bodyguard.

In December 1962, Jimmy opened his martial arts studio at the Midway Shopping Center in El Monte, California. In the early years, he called it “Karate Kung Fu” because no one knew what Kung Fu was at the time. He also opened up his studio to non-Asian students. He was the first to teach American students Chinese martial arts. He went by the name Jimmy to these American students, and referred to the art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot as Kung Fu San Soo. He used the term San Soo to reinforce the combat style of his art. Kung Fu San Soo has an emphasis in fighting, not the spiritual or healing aspects found in other martial arts. In January 1984, Jimmy H. Woo became Lo Sifu,³ Grandmaster, when his grandson, J.P. King, earned his black belt. J.P. marks the seventh generation of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot practitioners in Jimmy’s family. He achieved the level of San Soo Master in January 1993.

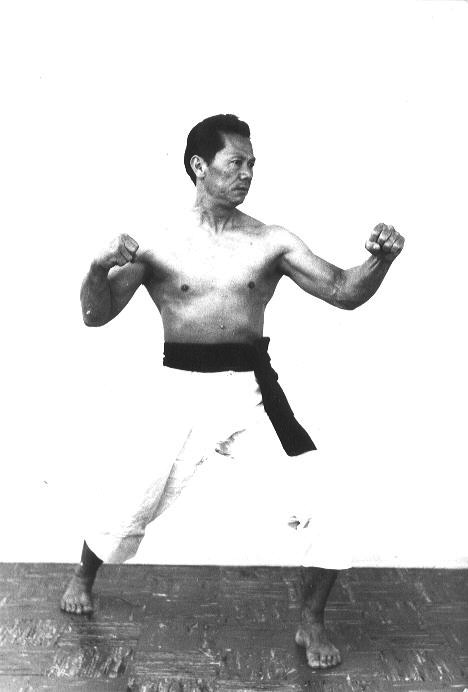

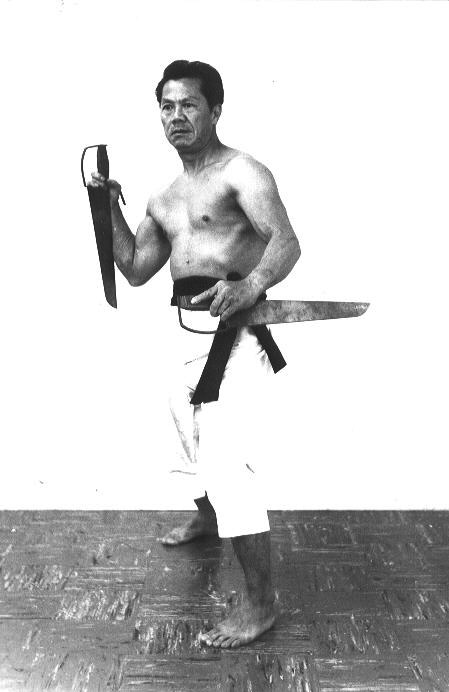

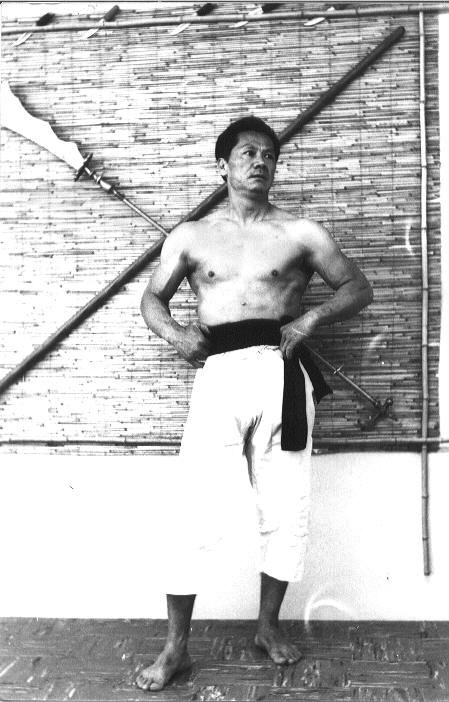

Destiny brought Chin Siu Dek to America, as Jimmy H. Woo, to preserve the ancient art of Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot. He taught his classes for 46 years in America, two Saturdays a month until 1991. Lo Sifu knew you could not mix other styles of fighting in with San Soo in order to keep the art of San Soo untainted. To add or take away from the art is to alter the very essence of Kung Fu San Soo. To alter San Soo is to say it was not complete to begin with, and anyone who saw Lo Si Fu teach and demonstrate it, could not make this claim. In his memory, the art must be preserved in its’ original form.

(Lo Sifu Chin Siu Dek) 老師傅陳壽爵

“You can take my life but not my confidence”

¹ Tsoi Li Ho Fut Hung Moy Sot (Tsoisonese), Cai Lî Hé Fó Xióng Wû Shù (Mandarin), Choi Léih Hòh Faht Hùhng Móuh Seuht (Cantonese); 蔡李何佛雄武術.

² Chin Siu Dek used the passport name Kun Haw Woo, later changed to Jimmy H. Woo at the request of an American teacher.

³ Lo Sifu (老師傅), meaning old or experienced Master.